I’ve been mulling over my response to The Cut’s, “It Must Be Nice to Be a West Village Girl” for a while now (to know me is to have sent me this article and asked me for my take on it).

I live in a luxury waterfront highrise in Williamsburg so I don’t have much of a leg to stand on in terms of having an opinion on the issues underscored in this article around gentrification.

Still, I’ll say this: I get the frustration around the displacement of POCs and the queer community, but I think the article misidentifies the problem. A neighborhood overrun by basic white girls isn't the cause, it's the effect. Focusing all your anger on 20-something girls in Alo Yoga sets sipping Aperol spritzes is kind of a cop-out when you could be redirecting your resentment towards the system that enabled it. But I digress.

Ultimately, I’m not the right person to be commenting on gentrification or the transformation of the West Village (I am a transplant after all). But neither are many of the other people who comment on it—ie. the people who interviewed for the article.

The thing that sticks out to me about the people who are critiquing societal shifts is that they’re not necessarily exempt from being part of the problem in the first place. And most of them are just as complicit in the changes they’re upset about.

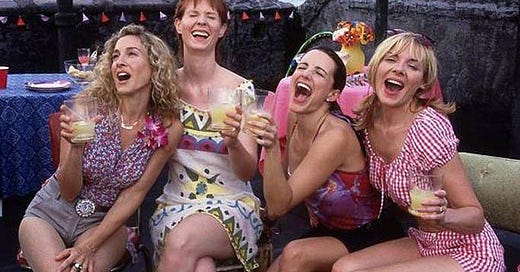

In the aforementioned article, one of the people interviewed is one of the “original” West Village Girls—a former Calvin Klein exec who bought a loft in 1997 that I picture as an IRL Samantha Jones, and whose main gripe is the lack of tables available at I Sodi or Via Carota.

I don’t imagine this woman has been the victim of gentrification. In fact, as one TikTok creator points out, the “original West Village girls” featured in this article are likely some of the first gentrifiers—again, think Samantha moving into her meatpacking apartment. That is to say, people who live in rent-stabilized glass townhouses on Grove Street shouldn’t throw stones.

But ultimately, I thought this woman complaining about the high-pitched frequencies of the current, younger residents just sounded bitter. And I realized a lot of the criticism around change, both in this article and in other aspects of life, is rooted in nostalgia.

Comparison is the thief of joy (even if it’s to your past life)

I recently touched on the danger of future tripping—worrying about what your career will become, what your house will look like, who you’ll marry, if you’ll have kids. But I think it’s just as easy, and unproductive, to get stuck in the past.

I have always considered myself someone who is very good at adapting quickly to change—good or bad. For better or worse, large life shifts don't typically phase me. I don’t linger for long on what could have been or what was.

I like to think I’m generally very accepting of my present, and I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the past.

But that’s not to say I’m immune to nostalgia now and then.

I’m nostalgic over my favorite summers. Over the trips and places I’ve traveled the made me feel most alive. Over memories where I’ve laughed so hard that my stomach hurt. Over friendships that have faded or changed. Over the street I lived on when I first moved to New York that reminded me every day I was where I was supposed to be.

I’m nostalgic over the holidays of my childhood, when we drove up to Vermont to stay in my aunts' cozy house on a small, snowy hill, stoking a wood-burning fire while their two sheepdogs sat at our feet. There was guitars and games and sledding down that small hill. I am so nostalgic over this, in fact, that I persuaded my family to spend Christmas in New Jersey this year instead of Florida—because I thought that if it was cold, it might feel the same as it used to and it might feel how Christmas is supposed to feel.

But I quickly regretted it. Because it was cold, and it wasn’t the same. And it never is when you try to recreate something.

That’s why I think when we focus too much on the past, and when we put too much emphasis on it, it can be detrimental. Because harping on the past signifies a lack in the present and suggests a distrust in the future.

But nostalgia doesn’t have to paralyze you. You can appreciate and miss the things that are gone without letting it cloud your expectations of your current reality. Or worse, keeping you stuck in an endless loop of longing for what can’t be recreated.

Instead, you have to adapt, accept things as they are, and move forward accordingly.

I’ve learned that the best thing I can do when I don’t like my current situation, when it’s lacking, is to do something about it. And I’ve always had a hard time understanding people who don’t like their situation and choose to do nothing instead.

You don’t like your job? Get a new one. You don’t like your boyfriend? Dump him. You don’t like your neighborhood because it’s overrun by influencers? Move to Brooklyn; it’s cheaper and greener

I know it’s not always that simple, but at the same time, it usually is.

The good old days are gone

I have to wonder if the chronically angry, nostalgic people who are so outwardly frustrated by the circumstances (eg. the retired “it girls” sneering at the current “it girls”) are just struggling with unfulfilled desires or deep dissatisfaction.

Maybe nostalgia is just a convenient cover for unhappiness—you’re not longing for a time that’s passed; you're projecting a desire to escape your current life.

But here’s the truth: things will never be the same as they once were. And it gets tiring hearing about how great things used to be.

New York won’t be the same as it was before Covid. We’ll never again know a world that didn’t have a criminally indicted reality TV star as president. Or return to a society that has yet to normalize robot therapists or self-driving cars. We’ll never experience children that won’t want smartphones the second their self awareness kicks in. Or wealthy people that won’t try to go to space for 11 minutes just because they can. We’ll never be able to relive our college glory days or resurrect Studio 54. And no, Montauk will never go back to being an old fishing village.

The West Village will never be an affordable, hidden gem.

I’ll also never get to experience another Christmas in that cozy Vermont cabin.

But we have to be okay with that.

The only version is the best version

I think of the book Midnight Library by Matt Haig, about a girl who gets the opportunity to experience all the versions of her life that were possible. In one life she’s an Olympic swimmer. In another she’s a famous musician in a rock band. In another she’s a glaciologist exploring the Arctic.

The takeaway for me was that every path has it’s ups and downs. Its good days and it’s bad days. Its pros and cons. Its joys and its tragedies.

And just like you can sentimentalize different versions of your life, looking back, things can seem so ideal. But there is always room to have gratitude for the now. And there’s always something to look forward to as well.

I don’t have all the answers, but every day I’m more convinced of the importance of staying present. Of not getting bent out of shape about the things you cannot change, and focusing on the things you can.

Being nostalgic is easy. What’s hard is making the decision to be positive and open to what’s to come. And knowing there is no other version of your life except for the one you’re living now, so you might as well make the best of it.

Suffice to say, I’ve decided I’m on board with a tropical location for Christmas this year.